Transcribing medieval manuscripts with TEI

It’s surprisingly difficult to make a transcription of a manuscript that is both readable and makes it easy to track what is on the page. This is an interpretative process that relies as much on the editor’s knowledge of Latin as of scribal conventions.

The Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) solves one of the problems from which humanists have long suffered in providing a standardized and technology-independent way to transcribe original documents. There are as many different conventions for rendering phenomena such as additions or substitutions as there are sub-disciplines. This hinders collaboration and impedes the availability of our work. Instead, we can take TEI files and display them however we want, or include them in text corpora.

- Finding the right character

- Anatomy of TEI tags

- Paragraphs and headings

- New pages, lines, and columns

- Stylistic features

- Additions

- Deletions

- Substitutions

- Abbreviations

- Damage

- Unclear or illegible letters

- Editorial interventions

- Quotations

- Names

This reference page shows how to transcribe common features of medieval manuscripts using TEI markup, tags that designate the relationship of textual elements to what surrounds them. This page only deals with the most basic elements for a documentary edition, based on the EpiDoc Guidelines and Digital Latin Library Guidelines. If you’re looking for a TEI element to represent a common feature, chances are that it exists. Part of the challenge in text encoding is knowing what not to record: we have established conventions for this in printed editions, but you need to have clear research questions and use your judgement to avoid being bogged down with too much markup.

If you need software for working with TEI, see my page on getting started with TEI and Atom. Digital Editing of Medieval Texts: A Textbook introduces TEI for all aspects of editing manuscripts. For a general introduction to TEI, see What is the Text Encoding Initiative?

Most of these illustrations are from my edition of the Miracles of St Frideswide (Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Digby 177) for the Digital Latin Library.

I follow the simple rule of taking account of every mark on the page, including the original punctuation, and adding TEI tags to show my interpretation – for example, using a tag to mark a phrase as a quotation instead of adding quotation marks. This principle makes it far easier to verify work and adjust it to the needs of different readers.

Finding the right character

Before you get started, take a step back and think about what you’re doing as you type. Every time you press a button on your keyboard, it transmits a numeric signal that the computer translates into a code in your file and displays as a readable letter. The standard for encoding these characters is Unicode.

It’s important that you get the Unicode right character for a professional appearance and accurate meaning. A common collection of characters as simple as −18°C (the temperature in Toronto as I write this) is surprisingly fraught: the minus sign (−), is just slightly wider than the hyphen one often sees (-), and the degree sign (°) is rounder than an ordinal indicator (º).

Shapecatcher allows you to draw a character and find the right one in Unicode. If you’re transcribing medieval punctuation, you will likely have to fudge things somewhat: Unicode only added something as common as the punctus elevatus in 2018, and still need to take other marks into account. The Medieval Unicode Font Initiative keeps track of these unusual characters; their character recommendation is a handy reference for finding Unicode characters through scholarly names.

Anatomy of TEI tags

Adding markup allows you to step beyond mere characters into interpretation. TEI a variant of XML (‘Extensible Markup Language’), a system that allows anyone to create their own markup languages. These use pre-defined series of tags that tell a computer how to interpret a file. This will be familiar if you’ve ever written a webpage, since XML looks just like the HTML (‘Hypertext Markup Language’) that underlies every webpage.

To tell the computer that there’s something different about a particular line of text, surround it with a tag. A typical problem is supplying letters that are omitted in a manuscript, which will typically appear in a book in the form of ⟨word⟩ or [word] – but in many contexts, the latter of these could instead indicate surplus letters that should be removed. To get around this problem, we can instead use a TEI tag. Normally, there is an opening tag and a closing tag, the letter beginning with a slash:

<supplied>word</supplied>

It’s faster, of course, to write [word]: the TEI tags simply offer a more explicit means of expressing the same thing. There’s nothing to stop you from writing that for your own purposes and running a find-and-replace operation once you’ve finished.

In other cases, however, we instead want to indicate features that can’t be applied to a string of text, but simply exist – such as an image, or the beginning of a line. These use a self-closing tag that ends with a slash. This example indicates that there is a line beginning in the middle of a word:

diu<lb break="no"/>tius

This example also shows an attribute, which allows you to attach extra information onto any tag. The break="no" attribute indicates that there is no break in the word, so the computer will know to add hyphenation when the document is displayed online or in print.

Note that XML will collapse any amount of white space (either spaces or line returns) into a single space. This means that you can add space wherever you like to make a file easier to read – but it also means that you need to add tags for any structural features. Adding two returns, for example, won’t create a paragraph; you need to use the <p> tag for that. These two examples will come out identically:

<p>A sentence with one space between each word.</p>

<p>

A sentence

with one

space between

each word.

</p>

Finally, you can add comments that you can read in the file but will not appear when the computer processes the file for readers. For example, you might make a note to yourself on an odd feature of a hand that you’d like to examine more closely:

utraque<!-- Why did the scribe write the abbreviation this way? -->

For more details on the structure of tags, see the W3Schools introduction to XML.

Paragraphs and headings

For a prose paragraph, use the <p> tag:

<p>

A paragraph.

</p>

The equivalent for poetry is <lg> (line group), with individual verse lines marked <l>:

<lg>

<l>Arma uirumque cano, Troiae qui primus ab oris</l>

<l>Italiam fato profugus Lauinaque uenit</l>

<l>litora – multum ille et terris iactatus et alto</l>

</lg>

To add a heading to a paragraph or group of paragraphs, use the <head> tag in combination with <div>:

<div type="textpart" subtype="book" n="1">

<head>In the name of Christ here begins the first book of the ecclesiastical history of Georgius Florentinus, known as Gregory, Bishop of Tours.</head>

<div type="textpart" subtype="section" n="1">

<head>In the name of Christ here begins Book I of the history.</head>

<p n="1">Proposing as I do ...</p>

<p n="2">From the Passion of our Lord until the death of Saint Martin four hundred and twelve years passed.</p>

<trailer>Here ends the first Book, which covers five thousand, five hundred and ninety-six years from the beginning of the world down to the death of Saint Martin.</trailer>

</div>

</div>

The <trailer> tag allows you to add a final rubric or explicit.

This example also demonstrates how to note section numbers in a text: the optional subtype="book" attribute indicates the type of division, and n="1" designates the number.

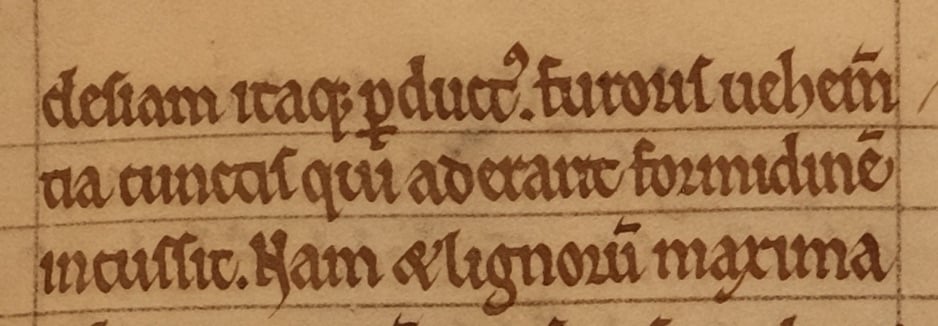

New pages, lines, and columns

Most editions based on a limited number of manuscripts provide folio and column references. Marking the beginning of each line in a transcription makes it much easier to look back at the manuscript, since it’s much quicker to look for a line beginning ‘incussit’ than search through an entire column for that word. It also makes it easier to check your work.

There are four tags for indicating one’s position in a source document:

ec<pb n="8r" break="no"/><cb n="a" break="no"/><lb break="no"/>clesiam itaque perductus. furoris

uehemen<lb break="no"/>tia cunctis qui aderant formidinem

<lb/>incussit. Nam et lignorum maxima

In this example, the n="8r" attribute indicates the label of a new page or column. Add break="no" to indicate that there is no break in the surrounding word. Starting a new line in the source file for each line in the manuscript makes verification easier, but has no effect on the final result.

This is equivalent to writing ‘ec|clesiam’ (with ‘8ra’ in the margin), ‘ec|8ra|clesiam’, or ‘ec-/8ra/-clesiam’.

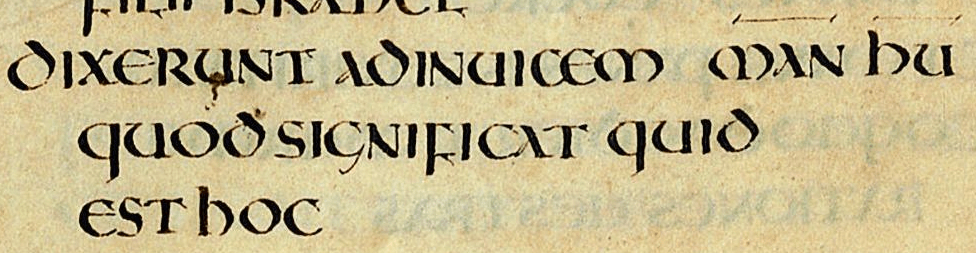

Stylistic features

There are many TEI elements for marking lists, different kinds of quotations, and emphasis; these are handy for showing your interpretation of a text. It can useful to keep track of the stylistic features in a manuscript that prompt you to use these.

For example, the scribes of the Codex Amiatinus like to draw a line above any foreign words. You can mark this in your text along with noting that it’s a word in a different language:

<lb/>dixerunt ad inuicem

<foreign xml:lang="he-latn" rend="supraline">man hu</foreign>

<lb rend="indent"/>quod significat quid

<lb rend="indent"/>est hoc

Here, rend="supraline" records the appearance of the foreign word in the manuscript. You can combine terms to indicate appearance; for example, if the word were written in red as well as having a line above it, you might write rend="supraline red". These terms can be whatever you like; these are often determined on a per-project basis. The rend attribute can be attached to almost any TEI element: I’ve also used it here on <lb> to indicate which lines are indented (which is key to knowing where new phrases begin in this manuscript).

If you’re marking a foreign word, it also makes sense to mark which language this is: you can add the xml:lang attribute to any tag, with standard language tags. (Use the Langage subtag lookup tool to find these.) Here, xml:lang="he-latn" indicates that this is Hebrew written in a Latin script.

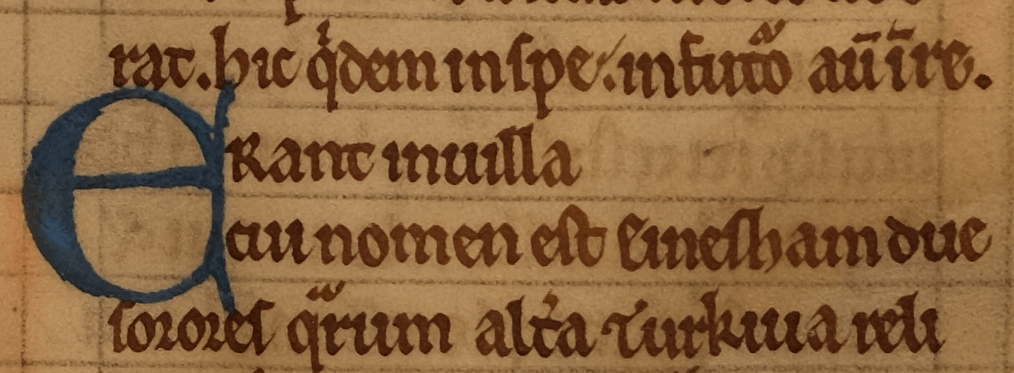

You will sometimes want to record a stylistic feature for its own sake. For instance, you might be determining the position of new paragraphs based on versals or drop capitals, and want to record this for your own purposes. If there is no other appropriate element, you can use the <hi> (highlighted) tag as a place to hang the rend attribute:

<hi rend="dropcap2 blue">E</hi>rant in uilla

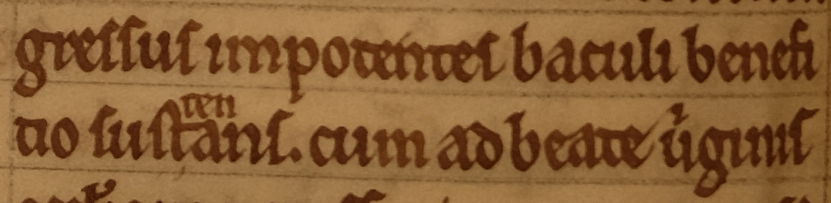

Additions

The <add> (addition) element allows you to note text added in a correction:

benefi<lb break="no"/>tio sus<add place="above">ten</add>tans.

cum ad beate uirginis

This is the equivalent of writing ‘sus\ten/tans’ or the critical note ‘sustentans] sustans MSa.c.’.

When noting an addition, it’s useful to mark its location, though this is optional. There is a set list of places in EpiDoc, with some overlap between them:

- above

- written above the line (superscript)

- below

- written below the line (subscript)

- bottom

- written in the margin at the foot of the page

- inline

- added within the line (probably squeezed between two characters or even adding a stroke to an existing character; compare overstrike)

- inRas

- added inline within an erasure

- interlinear

- written in an unspecified location between the lines, either above or below

- left

- written in the left margin

- margin

- written in an unspecified margin

- mixed

- written in more than one location

- opposite

- written on the facing page

- overleaf

- written on the other side of the page

- overstrike

- written over top of other written

- right

- written in the right margin

- top

- written in the top margin

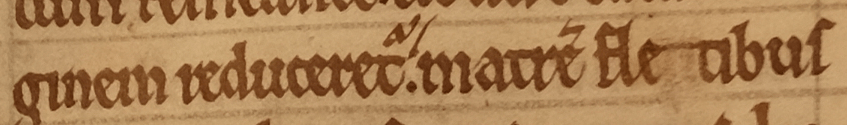

Deletions

The <del> (deletion) tag allows you to record letters removed from the text:

uir<lb break="no"/>ginem reduceretur⸵

matrem fle<del rend="erasure">n</del>tibus

This is the equivalent of adding the critical note ‘fletibus] flentibus MSa.c.’.

The rend attribute allows you to specify the appearance of a deletion. There is not a standardized list; I use the following:

- alteration

- letter modified (such as an n changed to an m); only used for substitution

- blackout

- text blacked over

- erasure

- text scraped or wiped from the page

- expunctuation

- dot added below text to indicate removal

- strikethrough

- text removed by drawing a line through them

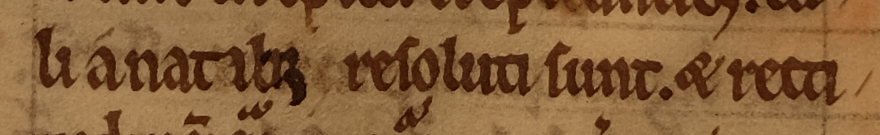

Substitutions

The <subst> (substitution) element groups additions and deletions to show their interaction:

ta<lb break="no"/>li a nat<subst>

<del rend="alteration">ali</del>

<del rend="erasure"><unclear>bus</unclear></del>

<add place="overstrike" hand="#black">ibus</add>

</subst> resoluti sunt. et

This is the equivalent of the critical note ‘natibus MS2 in ras.] natalibus MSa.c.’.

Here, the word ‘natibus’ was certainly another word beginning in ‘natali-‘; I used <unclear> to indicate that I think it was ‘natalibus’, but that I am not absolutely certain that those were the letters erased.

In this manuscript, there was a later corrector who worked through the text and made changes in a darker shade of ink: I used the hand attribute to associate the addition with other additions that I believe to be from the same hand.

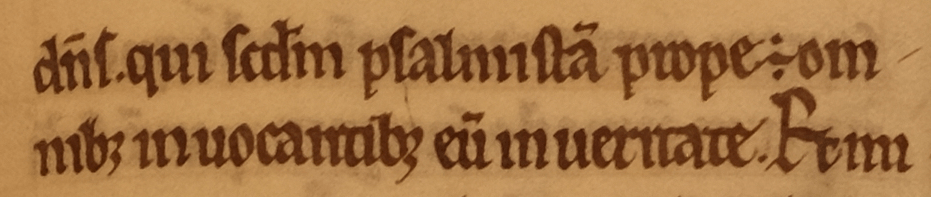

Abbreviations

The <ex> (editorial expansion) tag indicates letters that you have added to expand an abbreviation:

<lb/>d<ex>omi</ex>n<ex>u</ex>s. qui

s<ex>e</ex>c<ex>un</ex>d<ex>u</ex>m

psalmista<ex>m</ex> prope <ex>est</ex>

om<lb break="no"/>nib<ex>us</ex>

inuocantibus eu<ex>m</ex>

in ueritate. Et

This could appear in print with italics, underlining, brackets, or braces.

If you need to transcribe abbreviation character for graphic analysis, you can go further with the <expan> (expansion) tag (required in EpiDoc), which groups sets of <ex>, <am> (abbreviation marker), and <abbr> (abbreviation). This can quickly become difficult to manage; here is the same passage with the abbreviation characters transcribed:

<lb/><expan>d<ex>omi</ex>

<abbr rend="supraline">n</abbr>

<ex>u</ex>s</expan>. qui

<expan>s<ex>e</ex>c<ex>un</ex>

<abbr rend="stroke">d</abbr>

<ex>u</ex>m</expan>

<expan>psalmist<abbr rend="supraline">a</abbr>

<ex>m</ex>

</expan> prope

<expan>

<am>∻</am>

<ex>est</ex>

</expan>

<expan>om<lb break="no"/>nib<am>ꝫ</am>

<ex>us</ex>

</expan>

inuocantibus e<expan>

<abbr rend="supraline">u</abbr>

<ex>m</ex>

</expan> in ueritate. Et

Note also that there are multiple methods for marking abbreviations in TEI; this follows the EpiDoc style for expanding abbreviations.

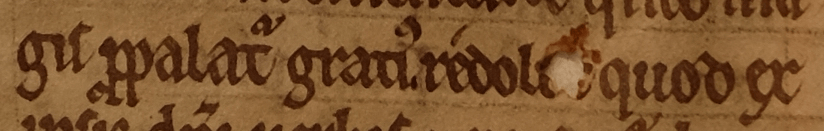

Damage

The <damage> tag indicates an area of the manuscript that has suffered harm. In this case, enough of the letters are still visible that you can still make out the meaning easily:

ma<lb break="no"/>gis propalatur gratius. redol<damage>et</damage> quod ex

If instead the ‘et’ were entirely absent from the manuscript, you could use the <supplied> tag:

redol<damage><supplied reason="lost">et</supplied></damage>

If you need to track a particular means of damage, you can use the agent attribute, such as <damage agent="water">.

Unclear or illegible letters

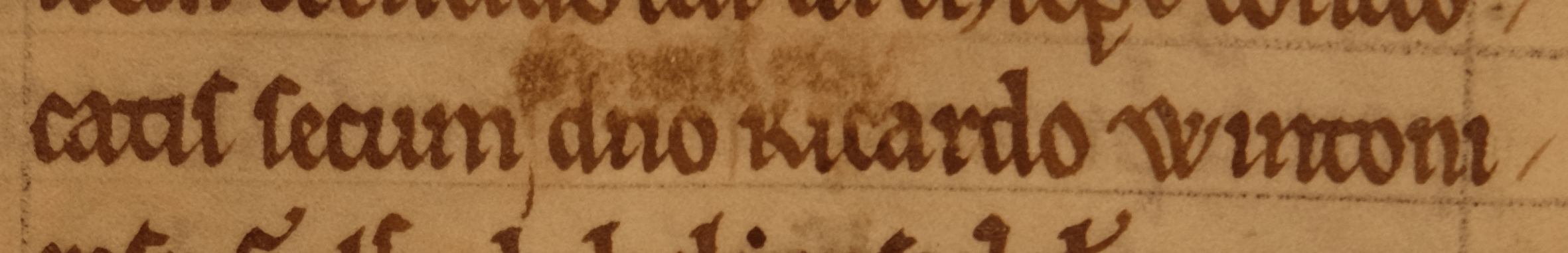

The <unclear> element marks letters that you have trouble reading. Here, a scribe added text above the line, but it was afterwards erased:

conuo<lb break="no"/>catis secum

<del rend="erasure">

<add place="above">

<unclear>predictis episcopis</unclear>

</add>

</del>

domino Ricardo Wintoni<lb break="no"/>ensi

I realized when editing this text that sorting out these erasures was crucial to dating the manuscript. But if you were in a hurry and simply wanted to mark that there were some illegible letters, you could use <gap>:

conuo<lb break="no"/>catis secum

<del rend="erasure">

<add place="above">

<gap reason="illegible" n="12" unit="character"/>

</add>

</del>

domino Ricardo Wintoni<lb break="no"/>ensi

Editorial interventions

The <supplied> tag marks letters that you or another editor added to the manuscript, either due to damage (as above) or because a scribe left them out:

qui uiuit et regna<supplied reason="omitted">t</supplied>

This is the equivalent of writing ‘regna⟨t⟩’ or ‘regna[t]’, depending on the publication style, or the critical note ‘regnat] regna MS’.

The <surplus> tag accomplishes the opposite, marking text in the manuscript for removal:

no<surplus>no</surplus>mine

This is the equivalent of writing ‘no[no]mine’ or the critical note ‘nomine] nonomine MS’.

You can also indicate the source for supplied or surplus letters, corresponding to entries in your TEI header (see the Digital Latin Library guidelines):

supra quam <supplied reason="omitted" source="#B">partem</supplied>

To record an editorial decision that replaces text in the manuscript, combine the <sic> and <corr> tags:

diuer<choice><sic>m</sic><corr source="#B">t</corr></choice>entes

Quotations

One of the best functions of TEI is its ability to distinguish between different types of quotations. This allows you to produce a reader’s edition showing quotation marks without adding more punctuation into the text that could be confused with characters written in the source manuscript.

You can use <q> as a generic method of adding interpretative quotation marks, but since it’s an expectation for a finished edition to mark quotations from another source (in an apparatus fontium or source apparatus) as well as dialogue or terms, it’s useful to use several tags for this purpose. You’ll likely only use the first two in most medieval Latin texts:

<quote>- for direct quotations of a text; use

<seg>to mark allusions where you do not want quotation marks to appear in the final version <said>- for dialogue

<mentioned>- for terms or phrases (usually only found in more technical texts)

<soCalled>- words that might appear in scare quotes or italics but are not attributed to a particular source (compare

<foreign>)

For example:

<said>Ne timeas</said> inquit <said>filia.

<quote>iacta cogitatum tuum in domino et ipse

te enutriet.</quote>

By marking your text in this way, it is absolutely clear what punctuation is present in the manuscript, and once you’re ready to create your source apparatus, you can simply search for every instance of <quote>. In simple situations, it is notionally possible to write the source information directly into your file using an attribute, such as <quote source="Ps54.23">, but there is not yet standard notation for this that produces a functional result.

Names

Marking names in a transcription has two major practical functions. Most importantly, it allows you to deal with people and places as linked data, associating names with an entity that a computer can understand. For example, if you linked all the places in your text to a gazetteer, you could then generate a map of all the places in your text.

Marking names also allows you to provide capitalization in a the reader’s version of your text without changing it in your source transcription. When I transcribe manuscripts, I seek to understand the rhetorical flow of the original, and pay close attention to capitalization and punctuation. This can often yield clues on who use the manuscript and how, but has also saved me from numerous mistakes in my editions. In many medieval manuscripts, a capital letter is the only way to tell where a new sentence begins. Rather than normalize proper nouns in my source file by adding capital letters, I find it easier to keep track of sentences as the scribe understood them if I transcribe capitalization exactly from the manuscript, then mark proper nouns with one of the TEI naming tags that I want to be capitalized in the normalized reader’s version.

You can use the generic <name> element, or you can use a more specific tag (mainly useful when making an index):

<geogName>- geographical features

<orgName>- organizations or groups

<persName>- people

<placeName>- places

You can add a link to an item in a dataset using the ref attribute. Wikidata is a great general reference point for people and places, because it in turn links to many other databases, but there many others. Pleiades, for example, is a gazetteer of places in the ancient world. For example, if you wanted to link to the Wikidata entry for London:

a <placeName ref="https://wikidata.org/wiki/Q84">londoniis</placeName> rediret

You can also link a phrase that is not a direct name using <rs> (referencing string). In this example, ‘beatissime uirginis limina’ refers to St Frideswide’s Priory, which is in Wikidata:

<rs type="place" ref="https://wikidata.org/wiki/Q3403092">beatissime uirginis limina</rs>